How and where will agents ship software?

Stepan Parunashvili, Nikita Prokopov·Jul 14th, 2025

We’re entering a new phase of software engineering. People are becoming addicted to agents. Beginners are vibe-coding apps and experts are maxing out their LLM subscriptions. This means that a lot more people are going to make a lot more apps, and for that we’re going to need new tools.

Today we’re releasing an API that gives you and your agents full-stack backends. Each backend comes with a database, a sync engine, auth tools, file storage, and presence.

Agents can use these tools to ship high-level code that’s easier for them to write and for humans to review. It’s all hosted on multi-tenant infrastructure, so you can spin up millions of databases in milliseconds. We have a demo at the end of this essay.

Let us explain exactly why we built this. We think that humans and agents can make the most progress when they have (1) built-in abstractions that (2) can be hosted efficiently and (3) expose data.

Built-in Abstractions

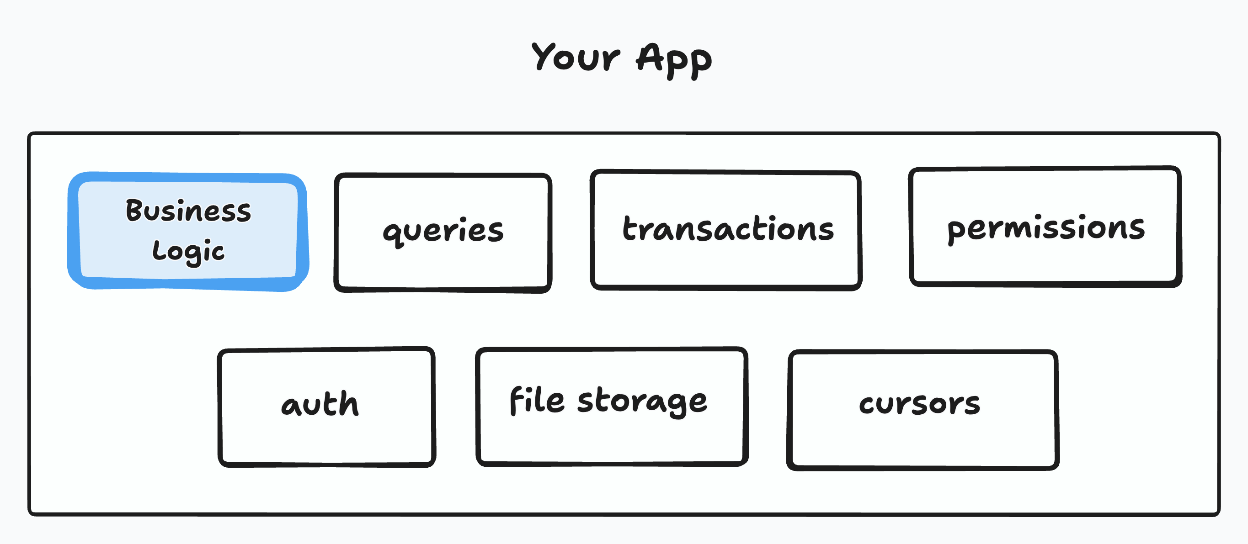

To build an app you write two kinds of code. The business logic that solves your specific problem, and the generic stuff that most apps have to take care of: authenticating users, making queries, running permissions, uploading files, and executing transactions.

These are simultaneously critical to get right, full of edge cases, and also not the differentiating factor for your app — unless they’re broken.

If all this work isn’t differentiating, why build it? When a good abstraction exists, it’s a waste of tokens to build it again.

And agents need good abstractions even more than human programmers do.

Locality

To make agents work well we need to manage their context windows. It’s very easy to break through limits. Especially when agents write code that involves multiple moving pieces.

Consider what happens when an agent adds a feature to a traditional client-server app. They change (a) the frontend (b) the backend and (c) the database. In order to safely make these changes, they have to remember more of the codebase and be exact about how things work together.

Good abstractions can combine multiple moving pieces into one piece. This is more conducive to local reasoning. The agent only has to concern themselves with a smaller interface, so they don’t have to remember so much. They can use less context and write higher-level code. And that’s great for humans too. After all we have to review the agent’s work. Shorter, higher-level code is easier to understand. [1]

And when both humans and agents make more progress, they build more apps. And when they build more apps, how will they host them?

Cost-Efficient Hosting

The dominant way to host applications has been to use virtual machines. VMs are efficient when you have a single app that serves many users. They’re inefficient when you have many apps that serve fewer users.

Overhead

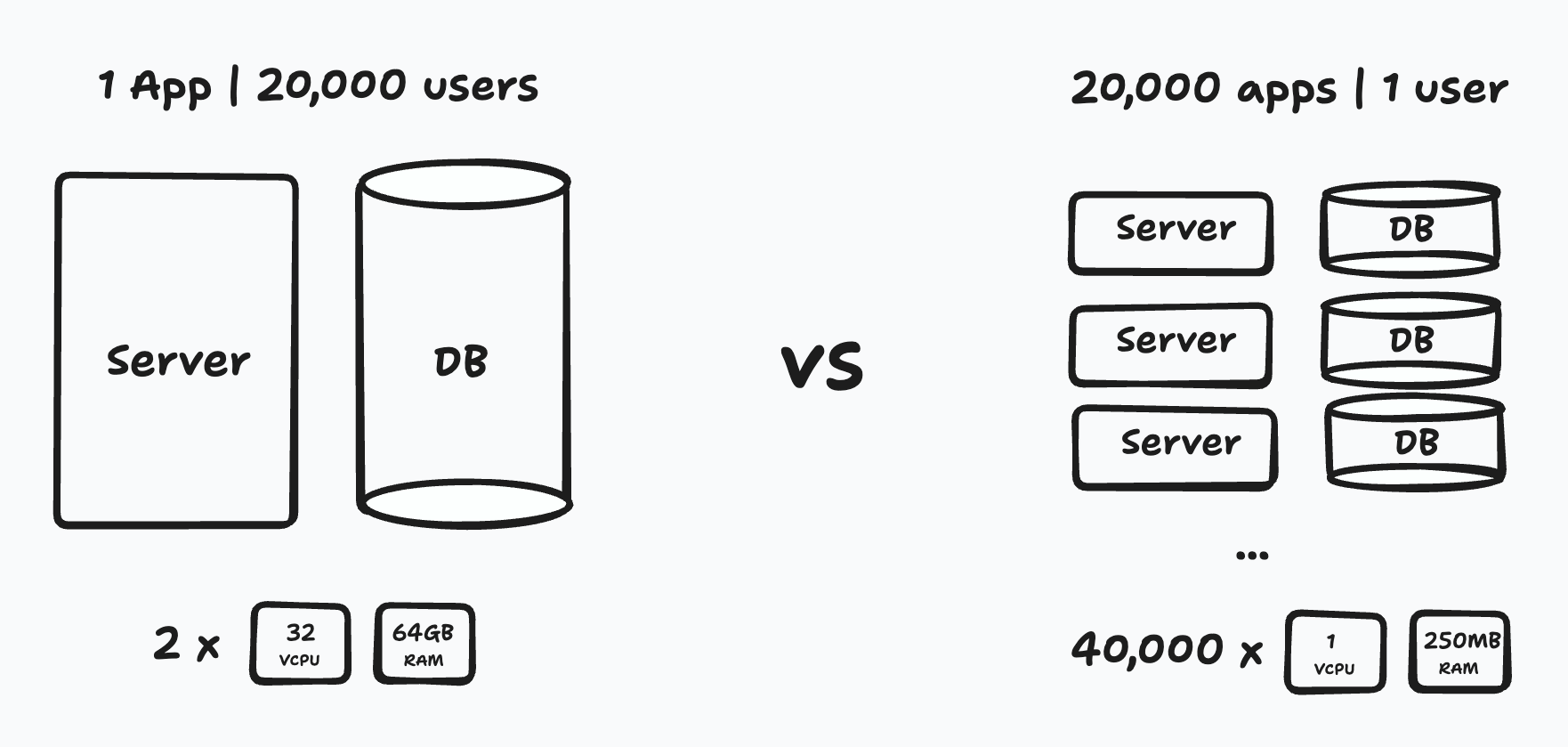

Let me illustrate with some napkin math. Consider 1 app that servers 20,000 active users, versus 20,000 apps that serve 1 active user:

For our 1 big app, we would need 2 beefy VMs. That’s about $800 a month. Not only is this affordable, but it makes for a fast app. Slow algorithms can take advantage of hefty CPUs and a lot more data can stay in memory.

For our 20,000 small apps we would need 40,000 VMs. That’s about $95,000 a month. Not only is this expensive, but it makes for slow apps. Slow algorithms would choke tiny CPUs and less data would stay in memory.

Friction

We’re not suggesting that people want to make 20,000 apps. We’re pointing out an inefficiency. Running applications today comes with overhead, particularly in RAM.

And when there’s overhead there’s friction. Today platforms freeze machines or limit how many apps you can spin up. In an era where every human can create lots of apps, this feels like a bummer.

Could we do better?

Getting Specific

Let’s think about why we needed VMs in the first place. VMs let programmers write code that’s arbitrarily different. But most apps aren’t arbitrarily different.

If we can get specific about what applications actually do, we can choose better isolation strategies.

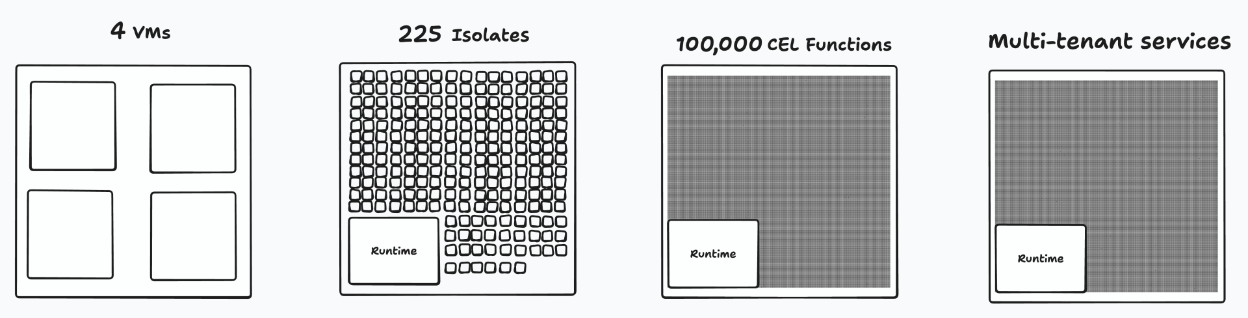

For example what if we knew that an agent didn’t have to use the GPU? We could skip traditional VMs and use Micro VMs [2] instead. That reduces the overhead by a few tens of megabytes of RAM, and lets us spin down inactive apps [3]. That’s better, but we can keep going.

What if we knew that an agent wanted to write Javascript functions? We could skip VMs and use V8 Isolates [4]. Each isolate takes about 3 megabytes of RAM. That’s 2 orders of magnitude more efficient. But we can still keep going.

What if we knew that agent wanted to write access controls? We could give them a more restricted language like CEL [5]. CEL only needs a few kilobytes of overhead per function. That’s close to 4 orders of magnitude more efficient than VMs. And we can still keep going.

What if the agent didn’t have to write any code at all? If we knew what the agent was trying to accomplish — say to authenticate users — we could give them a multi-tenant service which did that.

A maximally efficient future

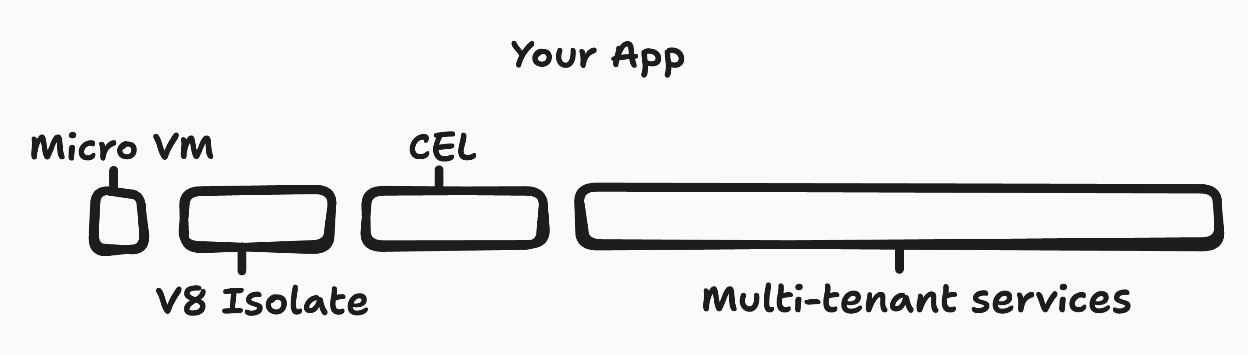

We can create efficient apps by choosing appropriate isolation strategies.

Shared abstractions could be served from multi-tenant services on big machines. Permissions could use CEL, javascript callbacks could run on V8 Isolates, and shell commands run on Micro VMs. If we did that, 20,000 apps with 1 active user would cost about the same as 1 app with 20,000 users.

Humans and agents would be able to deploy apps with little friction. Once these apps are deployed, how will people use them?

Exposed Data

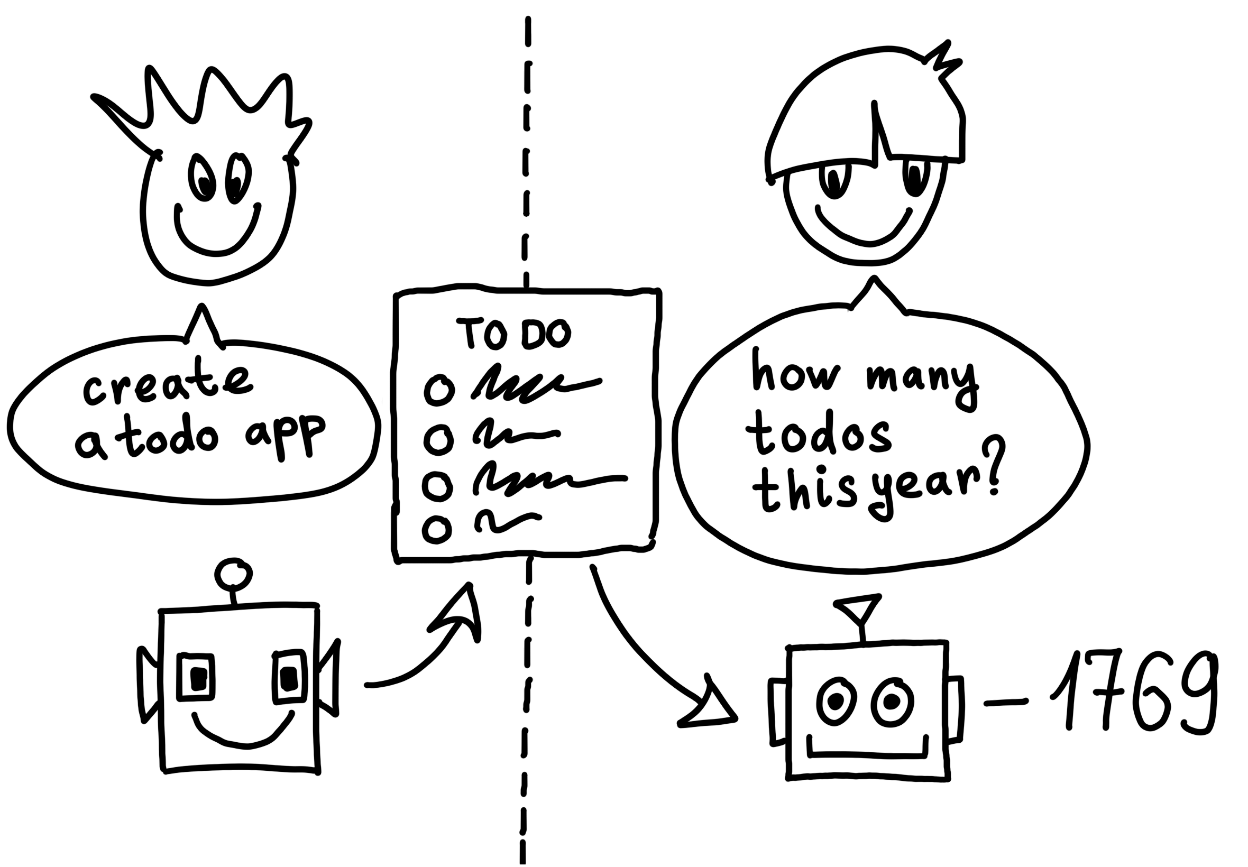

Traditionally, end-users were non-technical and would be stuck with whatever the application developer gave them. But now every user has an LLM too.

If one agent helps build the software, why shouldn’t another agent be able to extend it?

When every user has an agent, extendable software is an advantage. It’s in the application developer’s best interest: it can turn their apps into platforms, which are stickier. And it’s in the end-user’s best interest: they can get more out of their apps.

To make software extendable, developers generally used APIs. But APIs have a problem: application developers have to build them first. This means users are limited by what application developers thought were needed.

Databases are different. When apps are written on a database-like abstraction, users are free to make arbitrary queries and transactions. The application developer doesn’t have to foresee much. End-users can read and write whatever data they need to build all sorts of custom UIs [6].

And if that's true, database-like abstractions are going to be an advantage.

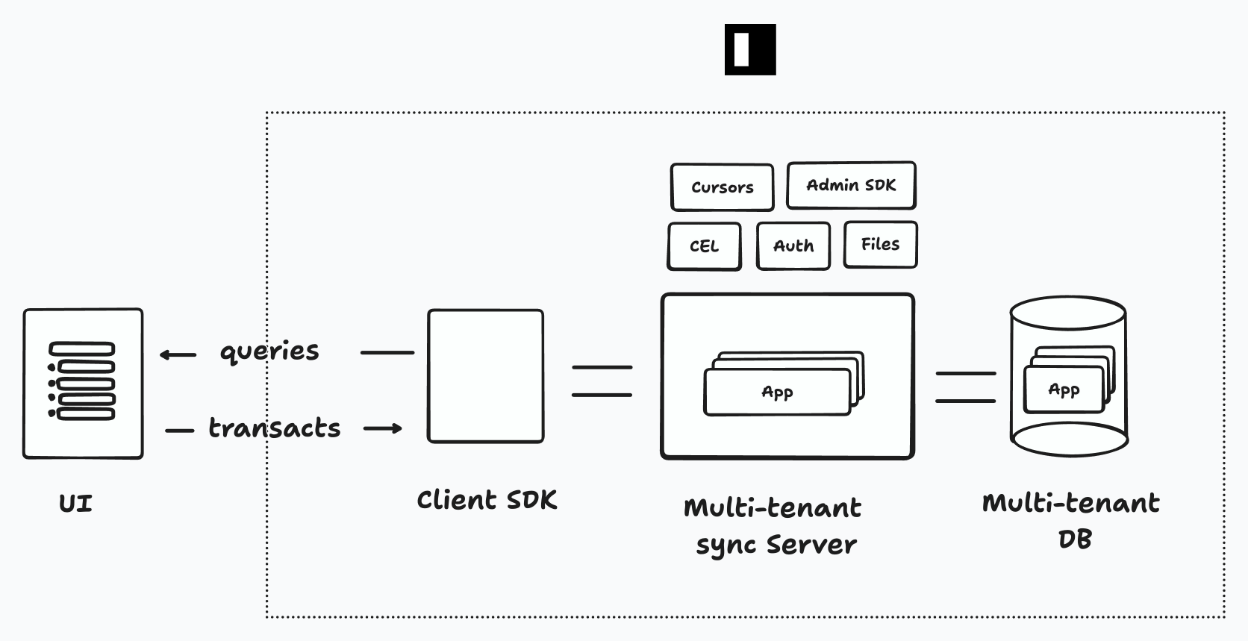

A Multi-Tenant Sync Engine

So if agents and humans work best when they have (1) built-in abstractions that are (2) hosted efficiently and (3) expose data, what infrastructure works best?

Let's start by thinking through what agents are good at. Agents are good at writing self-contained code. Code that they can reason about in one place, without too much extraneous state and edge cases. This is why the traditional client-server architecture is hard for them: it involves multiple parts that all need to work in unison — a server, a client, and a database.

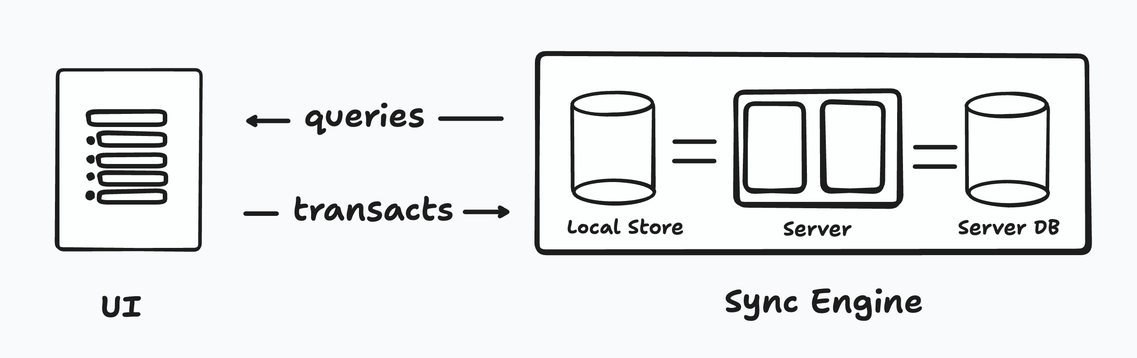

There are several ways to build self-contained apps. You can build a local-only desktop app (but then — no internet, multiple devices, or collaboration). You can build a server-only app (then you get latency, no offline mode, hosting costs). Or you could build a client-only app that treats the backend like a remote database.

In other words, a sync engine.

Sync engines let you work with data as if it was local and not worry about fetching it, persisting it, managing optimistic state, atomic transactions, retries and many other schleps. That’s a powerful abstraction (1).

Queries and transactions are straight-forward to sandbox. You can host them on multi-tenant platforms. Which makes for efficient apps (2).

And since you get a database-like abstraction, exposing data is relatively straightforward too (3).

That’s the future we are building Instant for.

A Tool for Builders

When we started Instant, agents were nowhere in sight. We focused on builders. Turns out if you design for builders, you end up making something good for agents too.

Builders want good abstractions. So we built a sync engine, permissions, auth, file storage, and ephemeral state (like cursors).

Builders also want efficient hosting. They have lots of projects, and it sucks when apps end up frozen. So we made our sync engine and database multi-tenant. This way we could offer a generous free tier.

Exposing the API

Instant is already great for builders. Real startups use Instant, and push upwards of 10,000 concurrent connections.

Today we're making it even easier. We're releasing three things:

- A platform SDK that lets you create new apps on demand

- A remote MCP server that makes it easy to integrate Instant in your editor.

- A set of Agent rules that teach LLMs how to use Instant

Put this together and you get a toolkit that lets humans and agents make more progress and do it efficiently. Let's try them out.

A habit tracker with dinosaurs

We’re going to build a habit tracker with one important twist: dinosaurs and aliens are going to be involved. And we'll build it right inside this essay.

If you keep pressing the buttons that follow, you’ll have an app you can play with at the end.

An example prompt

Before we continue, here's the prompt we gave Claude to generate all the code that follows:

Create a habit tracking app where users can create habits, mark daily completions, and visualize streaks. Include features for setting habit frequency (daily/weekly), viewing completion calendars, and tracking overall progress percentages. Make it all dinosaur and alien themed.

Keep the code to < 1000 lines.

We're going to wire this up to a real backend step-by-step.

Create a database

The first thing we'll ask our agent is to create a new database. It can use the MCP server to do that.

We’ve added a create-app tool right inside this essay. Click it, and we’ll spin up a new database.

instant

-

create-app

{ title: 'dino-habit-tracker' }

Click 'Run tool' to see the result.

(There's more in the essay!)

⎿

{

...

}

Thanks to Joe Averbukh, Daniel Woelfel, Alex Kotliarskyi, Ian Alejandro Sinnott, Cam Glynn, Anupam Batra, Predrag Gruevski, Irakli Popkhadze, Cody Breene, Kote Mushegiani, Nicole Garcia Fischer for reviewing drafts of this essay

Footnotes

-

We can probably make the review experience even better. If code is high-level enough, maybe we don’t need to show it. We could build UIs around abstractions and use them to summarize changes. ↩

-

To learn more, check out Firecracker ↩

-

Check out this essay from Cloudflare ↩

-

The CEL website is a good place to learn more. ↩

-

This opens up more questions. If you expose data, could you expose UIs too? What if every app shared their UI components. This is a bit too hazy to include in the essay, but it could make for an interesting experiment. ↩